Germinate- A Science Fiction Story About A *Diff*icult Superbug (Guest Author)

Day 32, 1843

Establishing our new home is proceeding reasonably smoothly, although the fauna is proving to be problematic.

Mathilde slowly creeps backwards, her eyes flitting between the Bacillupins approaching her. She’s forced to come to a stop as her back hits a wall. They have her cornered. Three pairs of fiery eyes blaze with ravenous hunger as the beasts close in on their prey, fur bristling and teeth bared. The woman’s grip tightens on her plasma blade, but she knows she can’t realistically fend off all of them.

Luckily for us, we have intelligence on our side.

Sweat beads on her forehead as the rancid smell of their breath coils in her nostrils . As their enormous paws edge forwards another step, a mechanical whirring begins. Their heads whip behind them before robotic appendages bind their jaws closed and ensnare their limbs. Collars laced with needle-tipped prongs snake around their throats and within seconds, they lay restrained on the ground.

“Mathilde! Are you okay?” Tara rounds the corner and rushes to her side, breathless as she cups Mathilde’s face and hastily examines her for wounds. Mathilde nods as she releases a breath. “I’m so sorry – the reports only just came through. I didn’t realise how close they’d gotten. I should’ve – ” Mathilde gently hushes her.

“Don’t worry. The most important thing is that I’m safe,” she turns her attention to the immobilised Bacillupins, “thanks to these robots of yours, of course. They’re neat, aren’t they?”

Tara beams, “They’re my newest model, the antibio-techs. These ones have infrared thermal imagers , and can be programmed to eliminate specific targets,” she gestures to the Bacillupins’ tightly bound jaws, “notice how they targeted the mouth first? The other day they dealt with the Caprylobacter that have been eating our crops, and they knew to target the horns and hooves to stop them from stampeding!”

“That’s really clever,” Mathilde nods approvingly, and pauses as she notices the rhythmic rise-and-fall of the Bacillupins’ chests cease. “Say, what’s going to happen to them?”

Tara smiles mischievously, “Let’s just say, they won’t be bothering us anymore.”

When Life Gives You Mould, Make Penicillin

We have all likely needed antibiotics to treat an infection at some point. These drugs, quite literally meaning “against life,” have revolutionised modern medicine and extended our lifespans by 23 years. Illnesses caused by bacteria, such as diarrhoea and pneumonia, were once leading causes of death but are now treatable. So, how did this substantial medical breakthrough come to be?

The use of antibiotics to treat infections dates back at least 3500 years. The Ebers Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian medical document and one of the oldest preserved medical works, contains several hundred remedies and incantations designed to treat illnesses and injuries. Among these, the use of mouldy bread, medicinal soil, and the yeast of sweet beer are included as wound remedies and treatments for infection. The medicinal use of moulds wasn’t restricted to ancient Egypt, either. In fact, the consumption of mouldy food and application of poultices has been widely used to treat infection and aid wound healing throughout history, including in Serbia, England, Greece, China, Australia, and Sudanese Nubia, in addition to being documented in the Jewish Talmud.

However, it wasn’t until the last century or so that scientists identified pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria as the causative agents of many infections, and these scientists began developing specific antibacterial compounds. The physician Paul Ehrlich worked extensively with dyes, contributing towards improving the detection and classification of bacteria. He noted that certain dyes could stain specific bacterial cells and biological structures, and proposed the idea of a “magic bullet” – that diseases could be specifically targeted without harming the patient. This principle would later influence the treatment of infections caused by pathogenic microorganisms as well as other diseases such as cancer. After rigorous testing, this work culminated in the development of arsphenamine (Salvarsan) in 1909, an arsenic-containing synthetic treatment for Treponema pallidum, which causes syphilis.

Inspired by Ehrlich’s work with dyes, the discovery of Salvarsan was followed by that of the sulphonamide Prontosil. Discovered by the bacteriologist Gerhard Domagk, this broad spectrum antibiotic could target two major classification groups of bacteria, and was successfully harnessed by Domagk to treat his 6-year old daughter of a streptococcal infection that threatened amputation of her arm and her life.

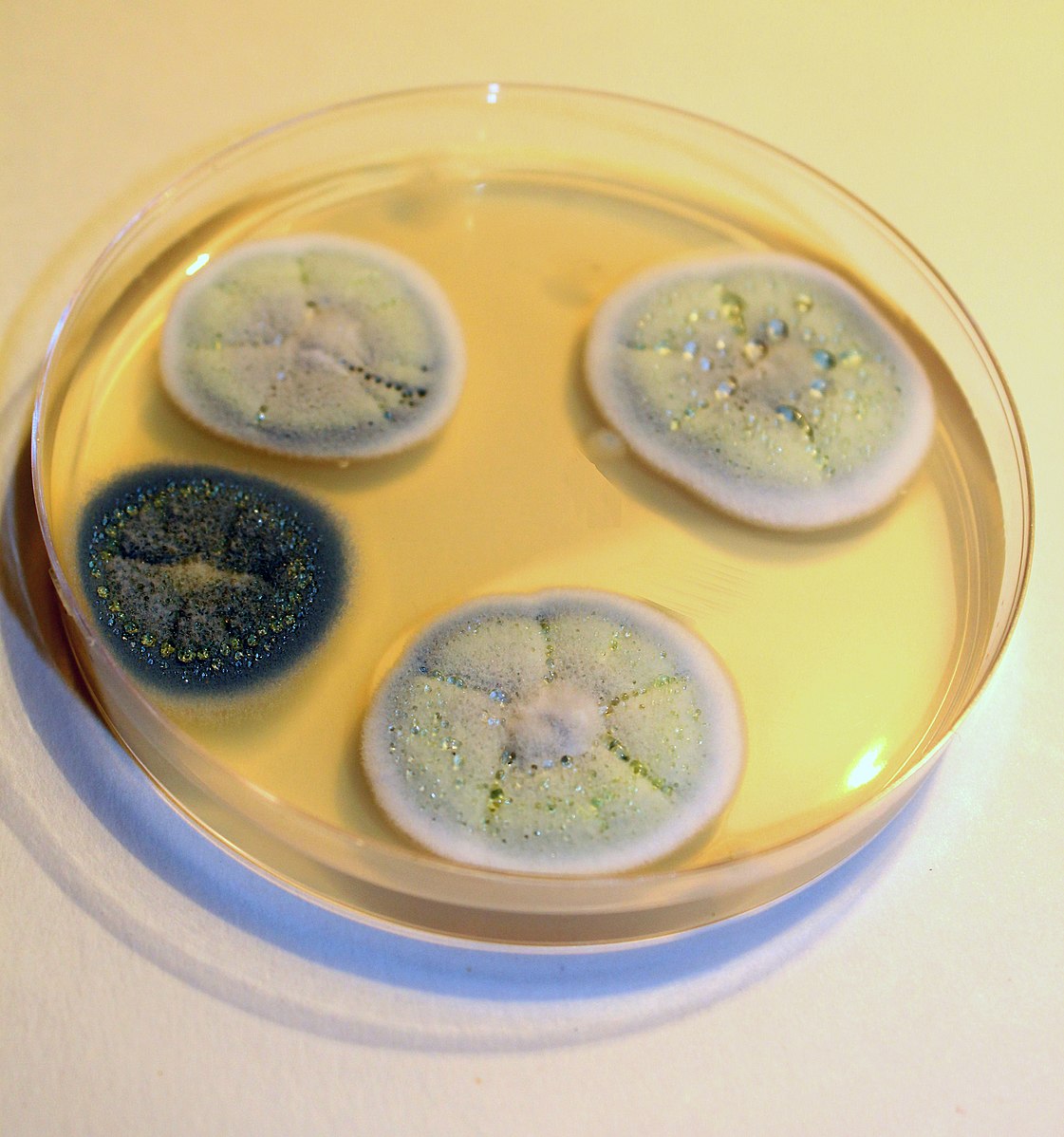

Although the development of Salvarsan sparked the antibiotic revolution, this drug— along with sulphonamides— were later superseded by the discovery of penicillin in 1928. A tale familiar to many, the fortuitous contamination of a Petri dish in Alexander Fleming’s lab with a species of Penicillium mould would come to kickstart the golden age of antibiotic discovery. Like the mouldy food used several thousands of years prior, the contaminating Penicillium prevented the growth of the staphylococcal culture on the Petri dish, which Fleming proposed was due to antibacterial “juice” produced by the mould rather than the mould itself. After diligent work from scientists Norman Heatley, Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, and their colleagues, the “mould juice”, named penicillin, was successfully purified.

So, What Does This Have To Do With Tara’s Robots?

Following the beginning of the golden age of antibiotic discovery, several new classes of antibiotics were discovered. While these drugs differ in their modes of action, they share the fact that they specifically target structures that are unique to bacteria, killing them or slowing down their growth while leaving human cells unharmed. Similarly, Tara’s robots specifically targeted the Bacillupins’ jaws and the Caprylobacters’ hooves and horns, subduing them and preventing them from continuing to cause problems.

Sounds great, right? While these wonder drugs have revolutionised medicine, it’s crucial that they are used responsibly. Antibiotics are fantastic at treating infections caused by pathogenic bacteria, however our bodies are also colonised with beneficial bacteria that play important roles in nutrition and health. This can be problematic, as antibiotics cannot necessarily distinguish between a harmful bacterium and a beneficial one, and so the latter can also be impacted by antibiotics. The result of this is that dysbiosis can occur – meaning the composition of the community of beneficial resident microorganisms is disrupted, which can have negative downstream effects on health.

With a reduction in microbial diversity comes a reduction in competition for nutrients, meaning microorganisms that usually wouldn’t get a look-in can exploit the imbalanced environment and take hold. As a result, the overgrowth of these opportunistic microorganisms can cause severe infections.

With this in mind, what might Tara’s antibio-techs do to harmless creatures minding their own business, but share qualities with Bacillupins and Caprylobacter?

Day 378, 1935

We are receiving reports of a bizarre new threat. There’s something… unsettling about these creatures.

Mathilde walks the lengths of the field, piling her basket high with plump tomatoes. Crop harvests have been bountiful ever since the pests were expertly wrangled by Tara’s antibio-techs. The constant thrum of robotic whirring in lieu of the chirps and chitters of wildlife took some getting used to, but it’s a small price to pay for safety.

Mathilde’s plasma blade remains fastened to her hip, but more through habit than through any necessity. “I really ought to polish the hilt,” she thinks to herself absently, and then immediately stops in her tracks. Something’s not right. The skin on the back of her neck prickles, and a knot forms in her stomach as she realises the field is silent. No antibio-techs to be heard.

She slowly turns to look behind her as she remembers the snarling teeth and snapping jaws, but is met with nothing but rows of towering vines. That is, until she blinks, and the very air before her sways. Scales clack as they rotate to lay flush against a grotesque reptilian body, unveiling the illusion. The creature’s wide maw opens, depositing the mangled and unresponsive remains of an antibio-tech.

They have camouflage abilities, resistance to our technology…

The breath catches in Mathilde’s throat as she stumbles backwards, momentarily frozen. Instinct then kicks in and she reaches for her weapon, activating the superheated plasma and diving forwards to sink the blade into the creature’s skull. To her horror, however, its flesh does not yield beneath her. Instead, it bears the blow unscathed, jerking its horned head to strike her to the ground with ease. She winces as blood pools and begins to soak her clothing, her plasma blade deactivating and clattering into the undergrowth.

…impenetrable armour…

Mathilde scrambles backwards, frantically trying to create distance between herself and the creature. Across the field, she hears the whir of a rapidly approaching antibio-tech and a fleeting sense of relief fills her – this should buy her some time. The robot advances, its lens rapidly scanning the threat and calculating an appropriate course of action.

… and, most concerningly, intelligence.

The creature considers the antibio-tech with astute eyes, carefully poised as it closes in with mechanical hands crackling with electricity. It mirrors the robot’s movement with startling precision, patiently waiting for a break in its defence before launching forwards a clawed hand to gore its lens. Disorientated, the antibio-tech spins, its hands haphazardly snapping at thin air before the creature bears down on its armoured metal body with a serrated tail. The exoskeleton bursts and spits forth gears and sparking wires.

Mathilde stares in horror, mouth agape. She presses her wounds with a trembling hand to stem the flow of the bleeding, gritting her teeth as she clambers to her feet. A chill runs through her as she considers what else the creature is capable of.

She flees.

We’ve named them Slayers.

The Gut, The Bad, And The Bugly

One such environment that is affected by dysbiosis is the gut, which is home to an enormous community of bacteria that play important roles such as helping us digest food, producing vitamins, and protecting us from infection. However, an imbalance in the community of gut bacteria can allow other, less savoury characters to take advantage of the disrupted environment and move in. One pathogen that is notorious for this is Clostridioides difficile.

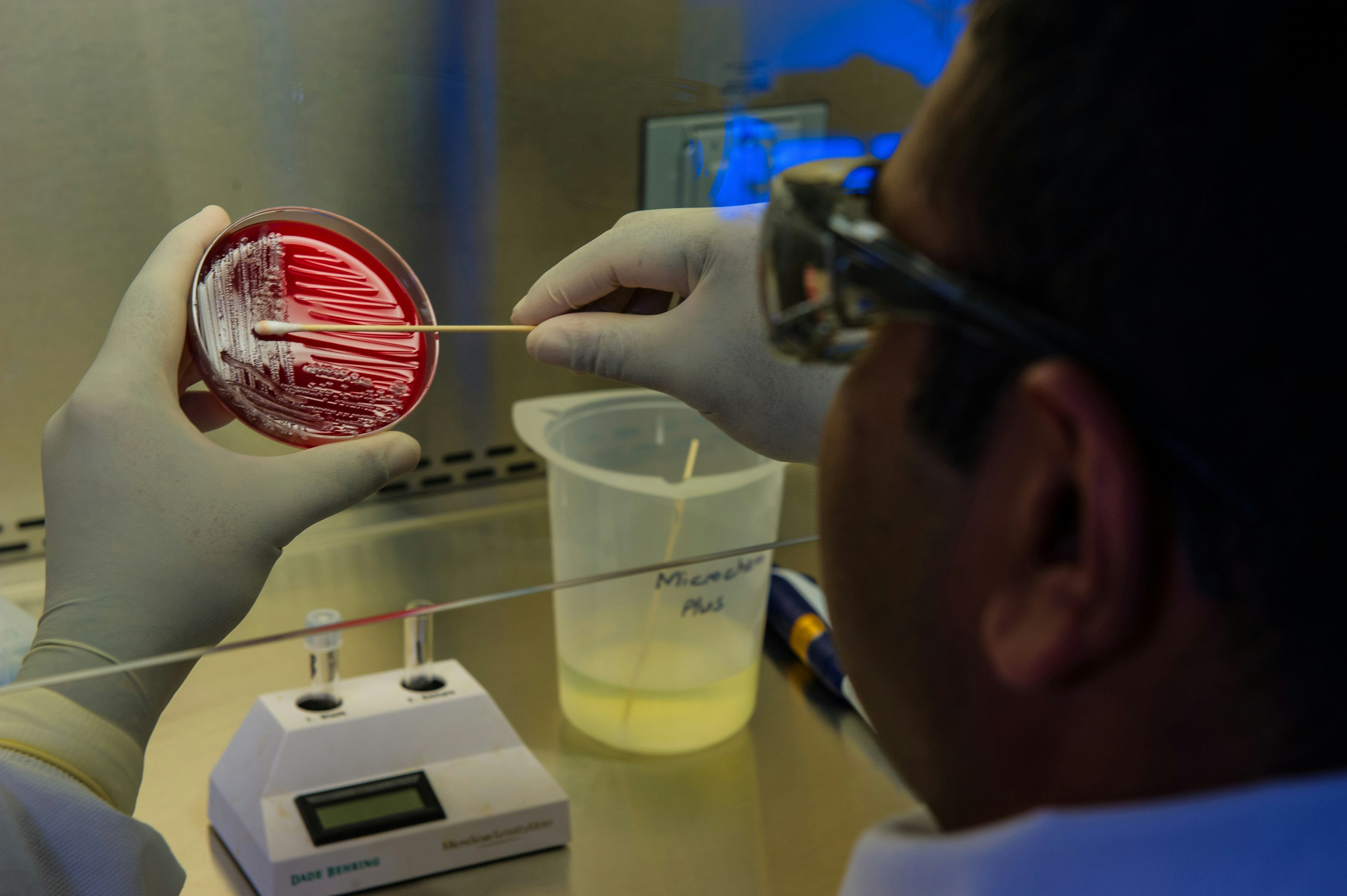

Clostridioides difficile, or C. diff, colonises the large intestine in the absence of a competing healthy community of resident bacteria. When allowed the opportunity to do so, it replicates inside the gut and produces toxins that damage it, resulting in classic symptoms of C. difficile infection such as diarrhoea, fever, and stomach pains. Infections can range in severity from mild diarrhoea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon that can rupture and result in sepsis (an extreme, improper response to infection that can cause organ failure), shock, and death.

C. diff is exceptionally good at what it does. Once an infection is established, they can be difficult to treat and are prone to recurring. For starters, C. diff infections are treated with antibiotics, which can continue to disrupt the population of resident gut bacteria. This creates a vicious cycle where C. diff can return and re-establish an infection straight after treatment, since the gut remains compromised and an ideal environment for it to move right back in.

C. diff’s ability to spread between patients and cause recurrent infections is attributed to its formation of spores. In this form, C. diff effectively goes to sleep, forming dormant (inactive) cells that are resistant to heat, radiation, and common disinfectants. This allows the bacterium to survive in the environment and withstand common cleaning methods until they are unwittingly ingested, at which point they wake back up again to continue wreaking havoc.

Even when it isn’t in spore form, C. diff is a hardy bacterium, with a chainmail-like outer surface layer (S-layer) that serves as protective armour against antibiotics and the immune system. Alongside this, C. diff remains one step ahead, adapting to treatment protocols by continually changing and developing various mechanisms to resist the effects of antibiotics. Due to this, scientists have deemed C. diff a “superbug” – a strain of bacteria that has become resistant to many antibiotics, with the Center for Disease Control (CDC) considering it to be an urgent threat.

Day 492, 2352

The rise of the Slayers has been devastating. Our crops are being decimated, our water sources contaminated, our buildings destroyed. Our people are growing hungry, countless lives are being lost, we are desperate…

Mathilde and Tara don’t often speak these days, their relationship tense and fractious. Trapped within the confines of their buildings, the atmosphere of grief and fear is suffocating. Tara spends her days cooped up in her workshop, hunched over her blueprints for hours on end as she frantically tries to optimise her antibio-techs to no avail. Mathilde, no longer able to safely wander the grounds, pores over books instead and loses herself in the history of ancient realms.

There is only one thing left for us to try.

Heavy-hearted, Tara begins to prepare an arsenal of her remaining antibio-techs as a last-ditch effort against the Slayers. If this fails, nothing more can be done except wait for them to inevitably breach the security of their buildings. She chews her lip and wrings her hands as she eyes the button that will launch the final assault. As she hesitantly reaches forwards to press it, the door to her workshop slams open.

“Stop! You’re making a huge mistake!” Startled, Tara immediately retracts her arm as a breathless Mathilde charges into the room. Wide-eyed and panting, she swipes an arm across Tara’s workbench to clear it, tools clattering to the ground as she throws down an open book in their place.

Tara glares incredulously, “Mathilde! What’s the meaning of this? Look at the mess you’ve just – ”

“Please, just read this,” Mathilde urgently taps the pages.

Tara crosses her arms and purses her lips, but yields as she turns her attention to the book with a heavy sigh. Her eyes widen as she reads about the experiences of a space-faring community quite like their own. A familiar tale of establishing a home on a new planet, disrupting the ecosystem, and as a result awakening an ancient dormant species that took advantage of the unoccupied ecological niche.

The blood drains from Tara’s face as she turns to Mathilde, “Does that mean my antibio-techs are responsible for the Slayers?”

Mathilde nods solemnly, “If this book is anything to go by, Slayers aren’t new creatures – in fact, they’ve existed for aeons, dormant and waiting for the perfect opportunity to emerge. The antibio-techs haven’t just been killing pests… they’ve also been killing the very creatures we need to keep the Slayers at bay.”

“No… it can’t be…”

“If we proceed with the attack as is… We’ll doom us all.”

Not All Hope is Lost

Although the rise of superbugs such as C. diff is a serious global health emergency, there is still hope. Researchers across the globe are working tirelessly to study antibiotic resistance and develop new treatments for multi-drug resistant infections. Alongside this, measures from the international to the individual patient level can be implemented, including responsible use of and equitable access to antibiotics, surveillance of antibiotic resistance, and improving infection prevention and control, to name but a few.

Coordinated, collaborative efforts are required worldwide to help slow the progression and minimise the impact of this growing threat – and we can all play a part.

Day 716, 1928

Our planned last-ditch assault on the Slayers has been halted - to proceed would be a fatal mistake. We must devise new ways of killing these creatures that don’t also harm the beneficial fauna, and restore balance to the ecosystem we’ve inadvertently disrupted.

Antibio-techs we are beginning to develop that are specifically targeted to the Slayers are looking promising, and as a result the fauna are starting to return and help drive these creatures back underground. Our future on this planet looks hopeful, and whenever the Slayers emerge next… we’ll be ready for them.

The sun bathes Mathilde’s shoulders as she plucks ripe fruit from the vines. The field is alive with the thrum of insects and the melodic trill of birdsong. In the undergrowth, small mammals chitter and scurry. As her gaze follows a scampering rodent, she spots a glint of metal amongst the vegetation. She approaches, and recognises it as the half-buried hilt of a familiar weapon.

“Hello, old friend,” she smiles, as she eases the plasma blade out of the ground and dusts the soil from it. As she fastens it to her hip, the scars on her stomach twinge, reminding her of her previous altercation with the Slayer. She thinks back to the event and a lump forms in her throat as she remembers just how close they were to losing it all.

Mathilde’s thoughts are interrupted as a flock of birds fly overhead. She takes a deep inhale, exhaling the aroma of summer flowers with a dreamy sigh. Never again would she take this beautiful, fragile ecosystem for granted, and they all have a role to play in keeping it safe.

Guest Author Bio:

@cgroughton on Twitter/X

Charlotte Roughton was a PhD student at Newcastle University in the UK who researched the molecular mechanisms of C. difficile sporulation, with the aim to further understand the fundamental biology of this superbug and identify alternative therapeutic avenues. Now, she works in higher education as a biological teaching technician, but microbes will always have a special place in her heart. In her free time, she is an avid crafter, D&D enthusiast, and devoted mother to her pet rats.

In its infancy, Germinate was the brainchild of Charlotte, her PhD supervisor Paula Salgado, and illustrator Jordan Collver. Originally intended for the Resist Now comic anthology, the tale sadly didn’t come to fruition. Years later, Charlotte decided to resurrect and flesh out the story for a written format.